Retouching and the Balance Between Preservation and Authenticity - Part 1

The restoration of paintings, particularly the practice of retouching, has been a contentious topic in art history and conservation for centuries. How do we balance the preservation of an artist’s original vision with the necessity of compensating for losses caused by time, neglect, or damage? This dilemma has sparked debates that span the philosophical, practical, and ethical dimensions of art conservation.

This article, the first in a two-part series, delves into the historical development of retouching practices, tracing key moments, figures, and ideas that shaped how art has been restored throughout the centuries. As someone deeply fascinated by both the technical and ethical aspects of art conservation, I find it remarkable how many of our contemporary debates about authenticity and preservation echo discussions from centuries ago. This exploration of retouching's history reveals not only changing techniques but also evolving attitudes towards art's preservation and authenticity.

First Voices: Early Debates on Restoration

The earliest documented criticism of art retouching comes from none other than Giorgio Vasari, the father of art history himself. In his biography of Luca Signorelli, Vasari's critique of Sodoma's restoration work on a damaged Christ Child reveals a fundamental tension that still resonates today: the challenge of recreating genius. His observation that it would be "better to keep works done by excellent men in a semi-damaged state than to have them retouched by some one less skilled" establishes a philosophical framework that would influence conservation thought for centuries to come. [1]

Vasari’s criticism encapsulates a fundamental truth about art restoration: the inherent impossibility of perfectly recreating another artist’s work, and more importantly, their authenticity. This observation speaks to the core of the retouching debate: can any restoration truly capture the artist's original vision, or does it inevitably alter the work?

The period following Vasari’s writings saw an interesting dichotomy develop. While intellectual discourse often echoed his scepticism about retouching, practical necessity demanded intervention to preserve valuable artworks. This tension between idealism and practicality became a defining characteristic of conservation history, one that continues to shape our field today.

Mimicry and Mastery

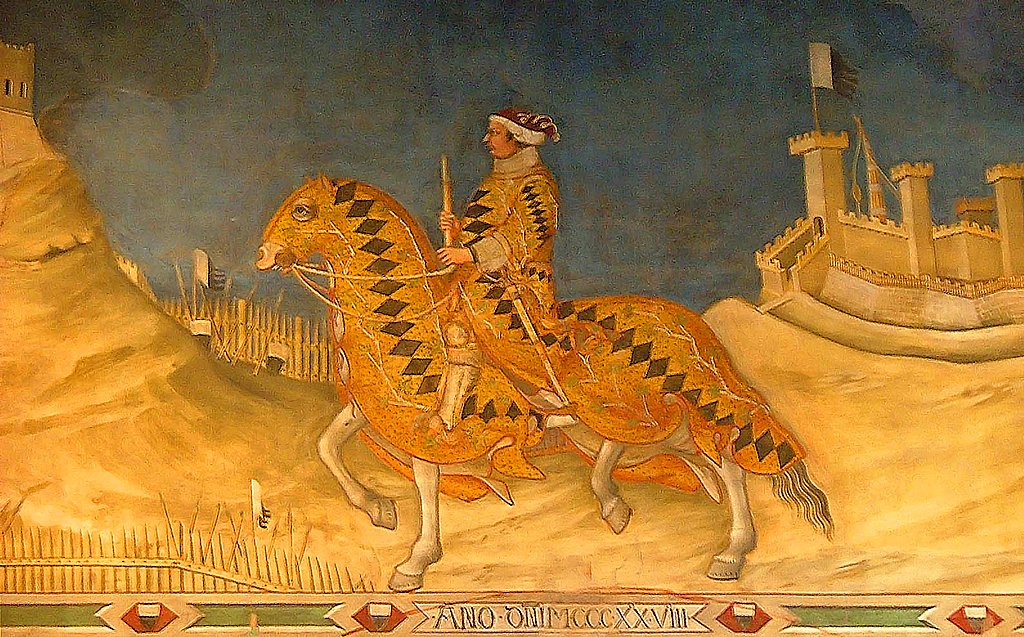

The emergence of retouching in the original artist’s style marks one of the most crucial developments in conservation history. The restoration of Simone Martini’s Guidoriccio da Fogliano fresco in Siena stands as a remarkable early example, where damaged sections were recreated in the original style, either 75 or 150 years after the initial painting. This restoration not only demonstrated the technical ability to mimic the artist's original style but also raised questions about the degree to which restorers could preserve the authenticity of the work without altering its original intent. [2,3]

Simone Martini (ca 1284-1344), Equestrian portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano (1328), fresco. Photo © Frans Vandewalle

In this case, the restoration was considered a significant achievement, reflecting the belief that retouching in the artist’s style was not merely a technical necessity but a means of honouring the original vision. However, this also marked the beginning of an enduring debate: could this mimicry be justified, or did it risk diluting the work’s authenticity with the conservators infleunce?

This period saw a fascinating evolution in restoration philosophy. While many paintings were still being "updated" to contemporary styles (a practice that makes conservators today shudder), there was a growing appreciation for maintaining artistic integrity. The case of the Bernando Daddi triptych provides an interesting counterpoint - here, the addition of a Christ Child about a century after the original creation wasn't so much restoration as reinterpretation. [4, 5] As someone deeply interested in ethical history, I find these early examples particularly thought-provoking because they force us to question where we draw the line between preservation and adaptation.

Today - ‘adding’ to a painting would be considered highly inappropriate. After the painting’s acquisition by the Getty Museum, examination revealed the child as a later addition and was removed as seen in the image below.

Bernardo Daddi (Italian, active about 1312 - 1348)The Virgin Mary with Saints Thomas Aquinas and Paul, about 1335. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Post-Conservation. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 93.PB.16

The Madonna of the Harpies by Andrea del Sarto (1517) represents what I consider a watershed moment in conservation history (pun intended). When the bottom fifth of the painting was destroyed in the Florence flood of 1557, the decision to reconstruct it in a manner faithful to the original marked an important milestone in conservation philosophy. [6]

Andrea del Sarto, Virgin and Child between St Francis of Assisi and St John the Evangelist ('Madonna of the Harpies'), 1517. Oil on Panel. Photo © Le Gallery Degli Uffixi

This restoration represents one of the earliest examples of what we might call "conservation consciousness" - an awareness of the importance of maintaining artistic integrity rather than simply updating works to contemporary tastes. What I find most remarkable about this case is how it anticipates modern conservation ethics by several centuries.

The Revolution of Reversibility

The concept of reversible retouching, which many might assume to be a modern innovation, actually has fascinating roots in the 17th century. Carlo Maratta's work on Raphael's Stanze in the Vatican and the Psyche Loggia at the Farnesina Palace introduces us to one of the first documented instances of consciously reversible restoration techniques. His use of pastels bound in gum arabic, specifically chosen for their removability, demonstrates a remarkably modern understanding of conservation ethics.

What I find particularly revolutionary about Maratta's approach is his recognition that future conservators might have better techniques or understanding - a humility that I believe should be central to all conservation work. The story of his work on Guido Reni's Madonna del Cucito fresco perfectly illustrates this principle. When Pope Innocent XI requested that the Madonna's neckline be made more modest, Maratta's solution - adding a veil in removable pastel - shows both technical innovation and ethical consideration. This solution balanced the demands and wants of his client with the respect for artistic integrity. [7,8]

Guido Reni, Detail: Madonna del Cucito, 1609. Fresco. Chapel of the Annunciation. Photo © Google Arts & Culture.

The discovery of late 18th-century pastel modifications in Giovanni Francesco Romanelli's fresco at the Louvre provides another fascinating example. The transformation of an allegory of Faith into Victory during the French Revolution, accomplished using removable materials, shows how this technique was used for both political as well as aesthetic purposes. [9,10] In my opinion, this case perfectly illustrates how conservation techniques often reflect broader cultural and social movements.

Practicality and Stability

The 18th century brought what I consider a revolutionary systematization to restoration, exemplified by the extraordinary work of Pietro Edwards in Venice. As Director of the Paintings Academy and Director of Restoration, Edwards established what might be considered the first professional standards for art conservation. His requirements for condition reports, environmental considerations, and proper training for restorers feel remarkably contemporary. What particularly impresses me about Edwards' approach is his holistic vision - he understood that successful conservation required not just technical skill, but also institutional support and professional standards. [11,12]

The French Revolution period presents what I consider one of the most fascinating case studies in the institutionalization of art conservation. The sudden responsibility for vast collections of confiscated art led to the formation of museum commissions and the development of more rigorous restoration standards.[13] Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun's 1794 call for chemists to develop new, stable retouching media represents an early example of cross-disciplinary collaboration in conservation science. [14,15] This period demonstrates how political upheaval can sometimes lead to unexpected advances in professional practices.

The search for stable materials during this period reveals an impressive understanding of conservation challenges that still resonate today. [16] Antoine-Joseph Pernety's 1757 recommendations for tempera or wax retouching show an early recognition of the problems with oil-based restoration - issues that would continue to challenge conservators for centuries.[17,18] What I find particularly noteworthy is how these early conservators were already grappling with problems we still haven't fully solved today.

Towards Modern Conservation

The 19th century marked what I believe to be the most significant shift toward modern conservation principles. The emergence of restoration literature as a distinct genre, with detailed handbooks and technical discussions, reflects the increasing professionalization of the field. The work of Christian Köster, Ulisse Forni, and Giovanni Secco Suardo established foundational principles that continue to influence conservation practice today.

What I find particularly significant about this period is the development of the "less is more" principle. This approach, advocating minimal intervention and visible restoration, represents a crucial shift in conservation philosophy. The statement by the Louvre's director in the 1860s that "Our mission is to show the masters as they are, to honor them with their strengths and weaknesses" encapsulates a modern approach to conservation that prioritizes authenticity over perfection. [19]

The period also saw increasing specialization and professionalization in conservation. The case of Jens Peter Möller, sent by the Royal Danish Academy to study restoration at the Louvre, illustrates the growing recognition that conservation required specialized training. [20] What I find particularly interesting is how this period saw the emergence of what we might call the "conservation ethic" - the idea that restorers needed not just technical skill but also a particular mindset and approach to their work.

The Rise of Conservation Science

One of the most significant developments of the 19th century, in my view, was the increasing integration of scientific knowledge into conservation practice. The recommendations for studying chemistry that began in the 1820s marked a crucial shift toward what we would now recognize as modern conservation science. Forni's recommendation of technical publications and chemistry texts shows an understanding that conservation required a broad base of knowledge. [21]

What I find particularly fascinating about this is how it balanced scientific advancement with artistic sensitivity. The debates over oil retouching perfectly illustrate this balance - while science could identify the problems with oil-based restoration, finding acceptable alternatives required both technical knowledge and artistic skill. This integration of science and art in conservation continues to be a crucial aspect of the field today.

Reflections on Historical Conservation

The history of art conservation reveals a striking continuity in our field's fundamental challenges. From Vasari's time to the present, conservators have grappled with the same core tensions: preservation versus restoration, reversibility versus permanence, and authenticity versus aesthetic unity. What's remarkable is not just the persistence of these questions, but how sophisticated early approaches to them often were. Maratta's reversible retouching techniques and Edwards' systematic methodology wouldn't seem out of place in a modern conservation studio.

Yet these historical approaches do more than just prefigure modern practices – they illuminate the philosophical nature of conservation itself. Each generation of conservators has faced the same essential question: what is our role in preserving artistic heritage? Are we caretakers, technical specialists, or interpreters of artistic intent? The delicate balance between preservation and intervention continues to define our field.

The infamous restoration of the Ecce Homo fresco in Spain exemplifies how these historical debates remain relevant today. This case, like many before it, forces us to confront questions about authenticity, intervention, and the limits of restoration. When does conservation cross the line into recreation? How do we honor both the artist's original vision and the artwork's historical journey?

As we look forward to Part 2 of this exploration, we'll examine how contemporary conservation practices build upon these historical foundations while adapting to new challenges and technologies. The principles established centuries ago continue to guide us, even as advancing technology and evolving cultural values reshape our approach to art conservation.

Author’s Note: I am trying a way of referencing that allows access to sources whilst hopefully maintain readability. I don’t necessarily think this is the best method and i’m considered alternatives such as linking an external file for those who want a full bibliography rather than links that may or may not work…let me know what you think.