Why Do People Dislike ‘Modern Art’? A Misunderstanding of Contemporary Art

Maurizio Cattelan, ‘Comedian’. Image taken from GQ, credits to Art Basel.

It’s a common sentiment: “Modern art is just a bunch of scribbles,” or “I could have done that!”—claims often accompanied by a dismissive eye roll. But what many people are actually reacting to isn’t modern art (which refers to a specific period from the late 19th to mid-20th century), but contemporary art—the broad and ever-evolving field of art being made today.

So why does contemporary art provoke such frustration? Is it the perceived lack of skill? The ambiguity? The belief that art should be beautiful rather than conceptual? In this article, we’ll explore why so many people feel alienated by contemporary art, how art has never been just about "pretty pictures," and some ways to start engaging with it more openly.

Historical Resistance to New Art Forms

Resistance to contemporary art is part of a long-standing pattern of public rejection of new artistic styles. When the Impressionists first exhibited their work in the 19th century, critics lambasted their loose brushwork and unconventional compositions, with Louis Leroy famously mocking Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) as nothing more than a rough sketch.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on Canvas. Image Credits.

Similarly, the rise of Cubism, championed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, was met with confusion and ridicule due to its fragmented forms and abandonment of perspective. Even Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionism was dismissed as meaningless splatters of paint rather than deliberate artistic expression. The discomfort with contemporary art today is thus a continuation of historical skepticism towards innovation in artistic practice.

Challenges in Engaging with Contemporary Art

There are several reasons why contemporary art remains a challenge for many audiences.

1. The Shift Away from Traditional Skill

One of the most common critiques of contemporary art is its perceived lack of technical ability. Classical art is often valued for its meticulous craftsmanship, as seen in the works of Caravaggio, Vermeer, or Bouguereau. In contrast, contemporary artists frequently prioritize concept over execution. Consider the works of Marcel Duchamp, whose Fountain (1917) — a signed urinal — challenged the notion of artistic authorship and craftsmanship.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz at 291 art gallery following the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, with entry tag visible. The backdrop is The Warriors by Marsden Hartley.

Similarly, the works of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt rely on instruction-based art, wherein the act of execution is often delegated to others. For those who equate artistry with manual skill, such works can appear trivial or undeserving of recognition.

2. The ‘Anyone Could Do That’ Mentality

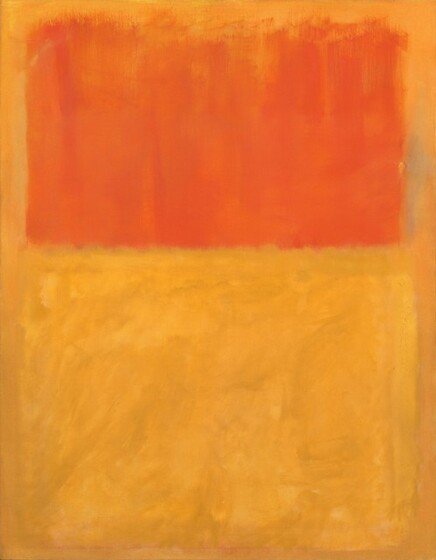

A frequent criticism of contemporary art is that it appears overly simplistic, leading to remarks such as "My child could do that." This reaction often arises in response to abstract or minimalist works, such as Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) or Mark Rothko’s color field paintings. While these works may appear simplistic at first glance, they are often deeply embedded in theoretical discourse.

Black Square, for example, was a radical rejection of representation in art, aligning with the Russian Suprematist movement’s emphasis on pure form. Rothko’s paintings, meanwhile, were intended to evoke deep emotional and spiritual responses, engaging with existentialist philosophy. Dismissing such works as simplistic overlooks the intellectual and historical contexts that inform them.

3. The Lack of a Clear Narrative

Traditional art often told stories, whether through religious iconography, mythological themes, or historical depictions. In contrast, contemporary art frequently embraces ambiguity, encouraging multiple interpretations. A work such as Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) — a preserved shark in a glass tank — may not offer a clear narrative but instead invites reflection on themes of mortality and impermanence.

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991. Tiger shark, glass, steel, 5% formaldehyde solution. Photo Credits.

Similarly, the installations of artists like Ai Weiwei or Kara Walker often function as critiques of political and social structures rather than as straightforward representations. The expectation that all art should “tell a story” in a conventional sense limits engagement with forms of artistic expression that prioritize concept over narrative.

4. A Resistance to the Unfamiliar

A significant factor in the rejection of contemporary art is the discomfort with new visual languages. Many contemporary artists deliberately challenge aesthetic norms, using unconventional materials, techniques, and mediums. Yoko Ono’s performance pieces, such as Cut Piece (1964), required audience participation, confronting viewers with ethical and psychological dilemmas.

Yoko Ono. Cut Piece (1964) performed by Yoko Ono in New Works of Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, March 21, 1965. Photo: Minoru Niizuma. Courtesy of Yoko Ono. © Minoru Niizuma 2015.

Similarly, Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019) — a banana duct-taped to a wall — was not intended as an object of beauty but as a satirical commentary on the absurdity of the art market. These works challenge viewers to engage beyond passive observation, prompting reflection on broader cultural issues.

How to Approach Contemporary Art with an Open Mind

For those who struggle to connect with contemporary art, there are strategies that can facilitate a deeper engagement:

1. Ask Questions Instead of Seeking Immediate Answers

Instead of dismissing a work as nonsensical, consider asking:

What does this make me think about?

Why might the artist have chosen this form or material?

What historical or social context informs this piece?

Engaging with contemporary art often requires an active process of inquiry.

2. Look Beyond Aesthetics

Not all art is intended to be visually pleasing. Some works aim to provoke, unsettle, or challenge existing perceptions. Rather than evaluating a piece solely based on its beauty, consider its conceptual or emotional impact.

3. Learn About the Artist’s Intentions

Exhibition labels, artist statements, and interviews can provide crucial insights into the motivations behind a work. For instance, understanding that Marina Abramović’s performance art is deeply rooted in endurance and the body’s limitations can transform one’s perception of her often extreme works.

4. Embrace the Experience Rather Than Seeking a Definitive Meaning

Art does not always need to be understood in a traditional sense. Some pieces function as sensory experiences rather than intellectual exercises. Olafur Eliasson’s large-scale installations, such as The Weather Project (2003) at Tate Modern, immerse viewers in light and atmosphere, creating a phenomenological encounter rather than a message-driven artwork.

5. Engage in Discussion

Sharing perspectives with others can broaden one’s understanding of contemporary art. Visiting galleries with friends, reading critical essays, or listening to artist talks can provide new insights that challenge initial impressions.

Final Thoughts

It’s okay to dislike certain works of contemporary art. Not every piece will resonate, and some may indeed feel absurd or superficial. But dismissing contemporary art as a whole because it doesn’t conform to past conventions limits the potential for meaningful engagement. The art world isn’t just about producing pretty pictures—it’s about ideas, experimentation, and pushing boundaries. And with a more open approach, you might just find something that challenges and enriches your perspective.